2020 // Ausstellung // Amor, erlegt und ausgeweidet: Militaria & Erotica mit kapitalistischer Prägung und feministischer Überzeugung.

see English version below

Das ist eine Nummer,

die untrennbar verbunden

ist mit Nationalismus,

Männlichkeit,

Waffenwahn

und Biertrinken

Interview mit Marcus Peter, Kunsthistoriker

Julia Kiehlmann: Wie kam Camouflage-Print in Mode? Was sagt das über die Gefühlswelt? Jemanden zu jagen oder zu töten ist ja eine extreme Form der Objektivierung.

MP: In Verbindung mit dem Titel KOcupid erweckt das bei mir den Anschein von gewaltsamer Aneignung dessen, was man begehrt.

JK: „Begehren heißt Objektivieren, heißt es sogar auf radikale Weise“, schreibt Barbara Sichtermann in ihrem Text Von einem Silbermesser zerteilt*. „[D]en Gegenstand ergreifen, halten, etwas mit ihm machen, ihn loslassen, ihn ansehen, ihn beurteilen“, dieses Bilden von Objekten wird Frauen historisch nicht zugestanden, sagt sie.

Genauso, wie das Objekt-sein, sich hingeben und bewundern lassen Männern nicht zugestanden wird: „Alles, was weich ist, was Lust ist, was Entspannung ist, muss bekämpft werden. Sich entspannen scheint identisch zu sein mit einer Kapitulation in dem immerwährenden Kampf, den ein deutscher Mann führen muss, um es zu bleiben“, schreibt Klaus Theweleit über die Folgen der soldatischen Prägung in Männerphantasien**.

Damit ist KOcupid vielleicht auch eine Ansage an Amor: Es reicht jetzt.

MP: Bis hierher und nicht weiter!

JK: Sieh, wohin du uns gebracht hast. Wir sagen dir den Kampf an, einer Vorstellung von Liebe, Beziehung und Geschlechterrollen, die so nicht funktioniert.

MP: Und dem damit verbundenen Erwartungsdruck. Der erschöpfte Cupid.

JK: Ich werte diskriminierende Strukturen im Verhältnis der Geschlechter als kriegerische Aggression und melde mich zum Einsatz.

Die Front verläuft dort, wo wir in Front zueinander gebracht werden, wo das Denken in sich ausschließenden Gegensätzen als einzige Möglichkeit angeboten wird. Propaganda, Waffen, Uniformen: Welcher Mittel können wir uns bedienen, ohne selbst Strategien der Unterdrückung anzuwenden?

Marcus, du trägst Camouflage-Socken.

MP: Ich habe sie geschenkt bekommen von meinen Eltern, die wissen, dass ich eine starke Verbindung zu Camouflage habe.

JK: Woher kommt die?

MP: Meine starke Verbindung zu Camouflage rührt daher, dass ich im Alter von ungefähr neun bis – ich würde sagen – vierzehn Jahren Berufssoldat werden wollte und mich für Militär interessiert habe. Für den Zweiten Weltkrieg, für modernes Militär, für die Wehrmacht, für die Rote Armee, die US-Armee, die Bundeswehr – alles! Technik, Strategien, Waffen.

Ich war auch für ein paar Jahre Mitglied im Schützenverein in meinem Dorf. Schießen war eine anhaltende Beschäftigung während der Kindheit und frühen Jugend.

Zuerst mit dem Luftgewehr im Garten und dann mit dem Kleinkalibergewehr im Schützenverein.

Schützenvereine sind ja wirklich das Evilste, was es gibt. Vielleicht sind schlagende nationalistische Burschenschaften noch schlimmer, aber ich glaube, Schützenvereine sind eigentlich nicht weit weg davon. Ich war Mitglied in so einem Schützenverein.

JK: Was meinst du mit evil?

MP: Sie sind nationalistisch. Der Ursprung der Schützenvereine in Deutschland liegt sehr häufig in den sogenannten Befreiungskriegen gegen Napoleon. Der Verein, in dem ich Mitglied war, hieß, nach seinem Gründungsjahr, Schützenverein Rothenburg / Saale 1815 e.V.; in den Vereinsräumen hing eine originale, zeitgenössische Gedenkflagge an den preußisch-österreichischem Krieg von 1866.

Das ist eine Nummer, die untrennbar verbunden ist mit Nationalismus, Männlichkeit, Waffenwahn und Biertrinken, und wenn die behaupten, sie seien harmlos, dann stimmt das nicht. Solche Schützenvereine sind vom Ansatz, vom Wesen her nicht harmlos.

JK: Du hast dich also früher für Kriegsbekleidung interessiert. Als ich dich kennenlernte, hast du Kunstgeschichte studiert und eine politische Haltung vertreten, die ich als links bezeichnen würde. Von der Zeit im Schützenverein geblieben ist eine Liebe zu Camouflage.

MP: Aber eine problematische Liebe natürlich. Diese umfängliche Faszination und Identifikation damit sind jetzt doch sehr anders und auch gebrochener.

Ich erkenne natürlich an, dass Camouflage in die Popkultur eingezogen ist, ungefähr mit den Hippies in den Sechzigern, mit Vietnamveteran*innen , die zurückgekehrt sind und immer noch ihre olivgrünen Parkas getragen haben. Dadurch ist das ein Objekt geworden, was auch in linkspolitischen, friedensbewegten Kreisen Verwendung gefunden hat, aber es ist natürlich gleichzeitig auch bei anderen Kräften noch immer in Verwendung: vom Militär einmal abgesehen, tragen das auch auf der popkulturellen Ebene Menschen mit unschönen Ansichten.

Deswegen habe ich meinen ehemals geliebten schwedischen Militärparka schon seit ungefähr drei Jahren nicht mehr getragen, weil ich das Gefühl habe, so richtig geht das nicht. Obwohl er wirklich ein sehr schönes Muster hat. An den Socken, da finde ich es noch okay, es ist nicht so offensichtlich und sie sind Super-Trash.

Deswegen habe ich meinen ehemals geliebten schwedischen Militärparka schon seit ungefähr drei Jahren nicht mehr getragen, weil ich das Gefühl habe, so richtig geht das nicht. Obwohl er wirklich ein sehr schönes Muster hat. An den Socken, da finde ich es noch okay, es ist nicht so offensichtlich und sie sind Super-Trash.

JK: Ist Camouflage ein Ausdruck von Naturliebe? Es wird ja hier auf deinen Socken in Kombination mit einem Naturmotiv abgebildet. Und du meintest, dass die blauen und gelben Streifen dich an Dienstabzeichen von Pfadfinder*innen erinnern – sind sie eine Vorform des Militärischen?

MP: Das ist breit gefächert, mit ein bisschen zu viel Sport und Drill ist man schnell beim Militärischen, aber es kann natürlich auch einfach ein Gemeinschaftserlebnis sein und naturnahe Begegnung. Aber was mich interessiert hat in der Jugend war eigentlich schon eher das Militär.

Ich bin auch immer mal wieder dabei, meine Kenntnisse ein bisschen zu aktualisieren, weil ich gemerkt habe, dass mein Wissen über den Stand der Militärtechnik mittlerweile sehr alt ist. Dann verbringe ich manchmal zwei Stunden bei Wikipedia und schaue, was es mittlerweile so an Schützenpanzern gibt, oder wohin sich zum Beispiel der Trend bei Camouflage entwickelt.

In den frühen Zweitausendern gab es eine Digital genannte Camouflage, welche verpixelt war, doch das wurde dann eher wieder abgelöst durch klassischere Muster.

JK: Von runden, organischen Formen?

MP: Ja, oder zersplitterten Formen, weil das Verpixelte sich offenbar als nicht so wirksam erwiesen hat.

JK: Schlechte Tarnung in der analogen Welt.

MP: Scheinbar ist der verschwimmende Effekt dort nicht so stark. Auch die Geschichte der Camouflage reicht meines Wissens nach zurück in die

sogenannten Befreiungskriege. Zu der Zeit sind Soldaten ja in grellen Farben herummarschiert, in Rot und Blau, und haben ideale Zielscheiben abgegeben. Das hat der damaligen Kriegsführung auch entsprochen, wo die Soldaten im Block aufeinander zu marschiert sind – man sieht das in dem Film Barry Lyndon von Stanley Kubrick sehr eindrücklich.

Gleichzeitig gab es aber sogenannte Jägerregimente, die sich in freierer Formation bewegen konnten und eher grün getragen haben. Da ist der Aspekt der Tarnung in die europäische Militärgeschichte hineingekommen und wurde immer weiterentwickelt, im Ersten und auch im Zweiten Weltkrieg.

Maßgeblich auch von den Nationalsozialisten, die haben unglaublich viel Forschung betrieben in dem Bereich und die bis heute gängigen Muster in ihren Grundformen schon entwickelt. Also alles, was heute an Camouflage zu finden ist, lässt sich auf die Forschungsergebnisse der Nazis in den Dreißigern und Vierzigern zurückführen, was natürlich super gruselig ist.

JK: Allerdings. Genauso unheimlich wie der Zusammenhang zwischen Populärkultur, Mode und Funktionskleidung für den Krieg.

MP: Der scheint absurd, aber Militärkleidung war die erste Konfektionskleidung, die in seriellen Größen hergestellt wurde, davor gab es nur maßgefertigte Kleidung.

Die Massenheere wurden dann mit konfektionierter Kleidung ausgestattet, und das ist der Punkt in der Geschichte, an dem das beginnt, was heute die Normalität darstellt. Das ist natürlich ein weiter Bogen, da sind ein paar Jahrhunderte dazwischen und es hat auch etwas mit Produktionstechnik und einer kapitalistischen Entwicklung zu tun, die auch eine militärische Entwicklung ist. Und dann noch die Camouflage drauf.

JK: Dann ist es sozusagen folgerichtig, weil die Standardisierung in der Bekleidungsindustrie, wie wir sie heute vorfinden, sich historisch entwickelt hat aus militärischen Strukturen?

Den Geschmack der Massen mitbestimmen, Trends aufgreifen und verarbeiten und gleichzeitig Normen setzen, was Größe, Maße, Gender angeht – welcheMode für welche Körper produziert wird, welche Körper überhaupt Berücksichtigung finden in dieser Produktion – das alles sind ja auch Normierungs- und Selektionsprozesse.

Ich habe mich der Camouflage aus einer Neugier und Faszination heraus gewidmet, die ich nicht ganz verstanden habe, sowohl bei anderen, als auch bei mir selbst. Es handelt sich um ein Massenphänomen. Es gibt alles in Camouflage. Und es gibt überall Leute, die das tragen und auch in allen gesellschaftlichen Schichten.

MP: Das kommt wahrscheinlich auf den Anwendungsbereich an. Der Milliardär auf Safari wird wahrscheinlich auch Camouflage tragen, aber im Alltag eher weniger.

Ich glaube, es ist schon auch mit einem sozialen Status verbunden, der auch damit zusammenhängt, dass diese Kleidung, zumindest solange es in Deutschland die Wehrpflicht gab, sehr billig zu haben war. Billige Kleidung, die haltbar ist und im besten Fall bequem.

JK: Das ist wahr für die Camouflage, welche tatsächlich Militärkleidung war und umfunktioniert oder im zivilen Rahmen getragen wurde, aber es gibt ja auch alles andere.

MP: Mir fällt jetzt kein Beispiel ein, wo ein teures Modehaus Camouflage verarbeitet hat, aber sicherlich, spätestens in den Achtzigern wurde das teuer verkauft.

JK: Mir fällt zum Beispiel Beyoncé ein, die in Camouflage aufgetreten ist. Ich stimme dir aber zu, dass man das eher mit einer Unterschichtenmode assoziiert. Der Schick des Prekariats, aber auch in der Mittelschicht gibt es hochwertige Kleidungsstücke, Prêt-à-porter-Modehäuser, die in guter Qualität zum Beispiel für den Herrn ein Camouflage-Jäckchen machen. Vielleicht keine Haute Couture –, aber wer weiß. Und: viel Frauenmode.

MP: Es ist wirklich merkwürdig, ich weiß gar nicht, ob es überhaupt im Militär Frauenkonfektionsgrößen gibt, oder ob es einheitlich ist. Wenn ich Bilder sehe von Soldatinnen, dann sieht es so aus, als hätten die einfach die gleichen Uniformen an.

Was natürlich den Anschein erwecken könnte, als hätte das Militär eine vereinheitlichende Funktion dahingehend. Natürlich ist es eine vereinheitlichende Zurichtung des Subjektes, aber Geschlechtsunterschiede werden im Militär ja definitiv nicht aufgehoben.

JK: Ich weiß gar nicht, seit wann in Deutschland Frauen zum Bund gehen können.

MP: Ich glaube, für Sanitätsberufe ging das schon immer, aus einer Tradition heraus, die sehr weit zurückreicht, und für den sogenannten Dienst an der Waffe seit den späten Neunzigern, glaube ich. Frauen waren natürlich zu der Zeit, als sie die Möglichkeit hatten, Dienst an der Waffe zu leisten, von der Wehrpflicht trotzdem befreit.

J: Als die Wehrpflicht in Deutschland abgeschafft wurde, oder ausgesetzt , nur die Einberufung pausiert ja, war das ein Moment, in dem Nachteile aufgrund des Geschlechts für Männer einmal öffentlich debattiert wurden. Das passiert selten, dabei gibt es sie auch, weniger in ökonomischen Angelegenheiten, aber dafür vermehrt in der emotionalen Entwicklung: Einschränkungen in der persönlichen Entfaltung, die Jungen aufgrund ihres Geschlechts widerfahren.

MP: Ich wäre mir gar nicht sicher, ob die Abschaffung der Wehrpflicht auch die Abschaffung eines Nachteils von Männern gegenüber Frauen bedeutet. Bis dahin bestand ja ein gesellschaftliches Interesse daran, dass es diese Wehrpflicht gibt, weil gleichzeitig der Zivildienst als Ersatzdienst eine stützende Funktion im Gesundheitswesen übernommen hat.

Und weil gleichzeitig Frauen durchaus die Möglichkeit hatten, freiwillig einen ähnlichen Dienst in einem Freiwilligen Sozialen Jahr oder einem Freiwilligen Sozialen Jahr Kultur zu verrichten. Ein Argument in der Debatte war, dass Männern gesagt wurde, ihnen entstünde kein Nachteil, weil sie nicht schwanger werden können und dadurch nicht vom Verdienstausfall betroffen seien, ihr Dienst an der Waffe würde das ausgleichen.

JK: Trotzdem finde ich es richtig, dass es keine Wehrpflicht mehr gibt, weil das trotzdem verbunden war mit Zwängen. Es bleibt ein Unterschied, ob man die Wahl hat oder nicht.

Ein Bekannter hat einmal von seiner Musterung erzählt und was für einen Eingriff in die körperliche Selbstbestimmung das für ihn bedeutet hat, sich vor jemandem, ohne das zu wollen, ausziehen und bewerten lassen zu müssen im Hinblick auf die Nutzbarkeit seines Körpers und Geistes für militärische Zwecke, bis hin zum Blick ins Poloch.

MP: Ich habe auch kein Mitleid mit der Bundeswehr, dass sie Nachwuchsprobleme hat, so weit zu gehen ist lächerlich. Gleichzeitig muss man aber auch sehen, dass es in Deutschland keine Tradition einer Freiwilligenarmee gibt, wie das in den USA der Fall ist.

Das stellt die Existenz der ohnehin schon fragwürdigen Institution Bundeswehr in Deutschland, mit ihrer problematischen Geschichte,

der Gründung aus der Wehrmacht heraus und der fehlenden Aufarbeitung, noch weiter infrage.

JK: Dafür gibt es die Modearmee von Leuten in Camouflage auf den Straßen. Es gibt sehr viel Frauenmode in Camouflage, das finde ich spannend. Ob das die Eroberung eines Feldes ist, von dem sie lange ausgeschlossen waren und wo sie es strukturell auch weiterhin schwerer haben, hineinzukommen oder zumindest, sich zu behaupten? Warum ist Camouflage so hip?

MP: Ich bin mir nicht sicher. Ich könnte mir vorstellen, dass es eigentlich ein Entgegenkommen in Richtung der Objektivierung durch den männlichen Blick ist. Es ist vielleicht zu banal, aber –.

JK: Warum, weil das ein Fetisch ist, eine Frau in Uniform?

MP: Ja genau, weil das einen Fetisch darstellt. Was fehlt Männern in Uniform? Eine Spindnixe in Uniform. Wobei eine Spindnixe natürlich eigentlich nicht so viel anhat.

JK: Es gibt aber Camouflage-BHs, es gibt Camouflage-Höschen, neben Oberbekleidung gibt es tatsächlich viele Dessous in diesem Muster.

MP: Was mir noch einfällt als Nachtrag zu der Frage nach Frauendienst an der Waffe: in Israel gibt es die Wehrpflicht für Frauen.

JK: Mindestens zwei Jahre, was eine richtig lange Zeit ist.

MP: In Deutschland waren es zuletzt neun Monate , in der Nationalen Volksarmee waren es 18 Monate und in der Roten Armee gab es im Zweiten Weltkrieg sehr viele Frauen, berühmte Scharfschützinnen, die dann auch propagandistisch überhöht wurden. Ich weiß nicht so viel darüber, aber ich könnte mir vorstellen, dass es auch aus einem kommunistischen Gleichheitswillen kam, Gleichstellung im Sinne von: alle sind männlich.

*Barbara Sichtermann: „Von einem Silbermesser zerteilt-“ Über die Schwierigkeiten für Frauen, Objekte zu bilden, und über die Folgen dieser Schwierigkeiten für die Liebe, aus: Weiblichkeit. Zur Politik des Privaten., Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin, 1983

**Klaus Theweleit: Männerphantasien, Bd. 1: Frauen, Fluten, Körper, Geschichte, Rowohlt, 1977

________________________________________

KOcupid // 2020 / Exhibition / Cupid, slewn and gutted: Military and erotic artifacts with a capitalist upbringing and a feminist conviction.

This folklore

is inseparably connected

to nationalism,

masculinity,

gun worship

and drinking beer

Interview with Marcus Peter, art historian

Julia Kiehlmann: How did camouflage print become fashionable? What light does that shed on the emotional world? Because hunting or killing someone are extreme forms of objectification.

MP: In connection with the title KOcupid, I get the impression of a violent appropriation of what one desires.

JK: „Desiring means objectifying, even means it in a radical way,“ writes Barbara Sichtermann in her text „Von einem Silbermesser zerteilt“*. „Grabbing an object, holding it, doing something with it, letting go of it, looking at it, judging it“, this kind of objectification is historically not allowed to women, she says.

Just as men are not allowed to offer themselves as objects of admiration, or to devote themselves: „Everything that is soft, that is pleasure, that is relaxation, must be fought. Relaxation seems to be identical with a capitulation in the perpetual struggle a German man has to fight to remain one“, writes author Klaus Theweleit about the consequences of soldierly conditioning in his book „Männerfantasien“**.

KOcupid is thus perhaps also an announcement to Cupid: Enough is enough.

MP: So far and no further!

JK: Look where we endet up. We challenge you and a concept of love, relationship and gender roles that doesn’t work out.

MP: And the pressure of expectation that comes with it. The exhausted Cupid.

JK: I consider discriminatory structures in the relationship between the sexes as warlike aggression and I’m reporting for duty.

The frontline is where we are made to front each other, where conceptualising in mutually exclusive opposites is offered as the only way to think and behave. Propaganda, weapons, uniforms: What means can we apply without using strategies of oppression ourselves?

Marcus, you are wearing camouflage socks.

MP: I got them as a gift from my parents, who know that I have a strong connection to camouflage.

JK: Where does this come from?

MP: My strong connection to camouflage originates from me wanting to become a professional soldier from the age of about nine to – I would say – fourteen years. I was interested in the military, as well; in the Second World War, in modern military, the Wehrmacht, the Red Army, the US Army, the Bundeswehr – everything! Technology, strategies, weapons.

I was also a member of the shooting club in my village for a few years. Shooting was an ongoing passtime during my childhood and early youth.

First with the air rifle in the garden and later with the small calibre rifle in the shooting club.

Shooting clubs are really the most evil thing there is. Maybe fencing students‘ corps are even worse, but I think shooting clubs are actually not far off. I was a member of one of those clubs.

JK: What do you mean by evil?

MP: They are nationalistic. The origin of the shooting clubs in Germany lies very often in the so-called wars of liberation against Napoleon. The club of which I was a member was called Schützenverein Rothenburg / Saale 1815 e.V. after its year of foundation; an original, contemporary commemorative flag of the Prussian-Austrian war of 1866 hung in the club rooms.

This folklore is inseparably connected to nationalism, masculinity, gun worship and drinking beer, and if they claim to be harmless, they are wrong. These rifle clubs are not harmless in their approach, not in their essence.

JK: So you used to be interested in war clothing. When I met you, you studied art history and had a political stance that I would describe as left-wing. What has remained from that time in the shooting club is a love of camouflage.

MP: But a problematic love, of course. The extensive fascination and identification with it is now very different and broken.

Of course I acknowledge that camouflage has made its way into popular culture, around the time of the hippies in the sixties, with Vietnam veterans returning and still wearing their olive green parkas. This made camouflage an object which has also been used in left-wing, pacifist circles, but it is of course also still in use by other forces: apart from the military, people with unattractive views also wear it in pop culture.

That’s why I haven’t worn my once beloved Swedish military parka for about three years now, because I feel that it’s kind of warped. Although it has a really beautiful pattern. On the socks, I do think it’s okay, it’s not too obvious and they are super-trash.

That’s why I haven’t worn my once beloved Swedish military parka for about three years now, because I feel that it’s kind of warped. Although it has a really beautiful pattern. On the socks, I do think it’s okay, it’s not too obvious and they are super-trash.

JK: Is camouflage an expression of love of nature? It is shown here on your socks in combination with a nature motif. And you said that the blue and yellow stripes remind you of scouts‘ badges – are they a prequel of the military?

MP: It’s a wide range of activities, with a little too much sport and drill you’ll quickly get into the military, but of course it can also simply be a community experience and a close encounter with nature. But what interested me in my youth was actually more the military.

I’m always updating my ken, because I noticed that my knowledge of the state of military technology is outdated. So I sometimes spend two hours on Wikipedia to see what kind of infantry fighting vehicles there are now, or where, for example, the trend in camouflage is heading.

In the early two-thousanders there was a camouflage called „Digital“, which was pixelated, but it was replaced again by more classical patterns.

JK: By round, organic shapes?

MP: Yes, or fragmented forms, because the pixelated one apparently proved to be less effective.

JK: Bad camouflage in the analogue world.

MP: Apparently the blurring effect is not so strong there. From what I know, the history of camouflage also goes back to the so-called wars of liberation. At that time, soldiers marched around in bright colours, red and blue, thus presenting ideal targets. This corresponded with the warfare of the time, where soldiers marched towards each other in a block – you can see this very impressively in Stanley Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon.

At the same time, however, there were so-called fighter regiments, which could move in a more open formation and tended to wear green. This is where the aspect of camouflage became part of European military history and then was developed further in the First and also in the Second World War.

The National Socialists also played a decisive role in this, as they carried out an incredible amount of research in this area and have developed the basic forms of the patterns that are still in use today. So everything that can be found in camouflage today can be traced back to the research results of the Nazis in the thirties and forties, which is of course super creepy.

JK: Indeed. Just as scary as the connection between popular culture, fashion and functional clothing for war.

MP: It seems absurd, but military clothing was the first ready-made clothing to be produced in serial sizes, before that, there was merely made-to-measure clothing.

The mass armies were then equipped with ready-made clothing, and this is the vantage point in history for what is considered normal today. That is of course a wide arc, there are a few centuries in between and production technology and a capitalist development do play a role therein, but they are a military development, as well. And then there is the camouflage on top of it.

JK: So it is consequentially, because standardisation in the clothing industry, as we find it today, has historically developed from military structures?

To help determine the tastes of the masses, to pick up and process trends and at the same time set standards in terms of size, measurements, gender – which fashion is produced for which bodies, which bodies are considered in this production – all this are processes of standardisation and selection.

I dedicated myself to camouflage out of a curiosity and fascination that I did not fully understand, both from others and from myself. It is a mass phenomenon. Everything exists in camouflage. And there are people everywhere who wear it and also in all social classes.

MP: It probably depends on the area of application. The billionaire on safari will probably also wear camouflage, but in everyday life rather less.

I think it’s also associated with a social status, which may derive from the fact that these clothes were very cheap, at least as long as there was compulsory military service in Germany. Cheap clothes which are durable and, at best, comfortable.

JK: That’s true for camouflage that was actually military clothing and was converted to or worn in a civilian context, but then there’s everything else.

MP: I can’t think of any example now where an expensive fashion house processed camouflage, but certainly, by the eighties at the latest, it was sold at a high price.

JK: I remember Beyoncé, for example, who performed in camouflage. But I agree with you that it might be more associated with lower class fashion. The chic of the precariat, but also in the middle class, there are high-quality garments, prêt-à-porter fashion houses that make for example a camouflage jacket for men, in fair quality. Maybe not haute couture – but who knows. And: lots of women’s fashion.

MP: It’s really strange, I don’t even know if there are women’s clothing sizes in the military at all, or if it is uniform. When I see pictures of female soldiers, it looks as if they simply wear the same uniforms.

Which could of course make it seem as if the military has a unifying function in this respect. Of course it is a unifying dressing of the subject, but gender differences are definitely not abolished in the military.

JK: I don’t know since when women can join the army in Germany.

MP: I think it has always been possible for medical professions, from a tradition that goes back a long way, and for the so-called service at arms since the late nineties, I think. Women were, of course, still exempt from compulsory military service at the time when they had the opportunity to serve at gunpoint.

J: When conscription was abolished in Germany, or suspended, after all it was only paused, that was a moment when disadvantages based on gender for men were once publicly debated, which happens rarely. They seem to exist less in economic matters, but more in terms of emotional development: restrictions in personal development that boys experience because of their sex.

MP: I would not be sure at all whether the abolition of conscription also meant the abolition of a disadvantage of men compared to women. Until then, there was a social interest in the existence of compulsory military service, because at the same time alternative civilian service had taken on a supporting function in the health system.

Meanwhile, women had the opportunity to volunteer for a similar service in a Voluntary Social Year or a Voluntary Social Year of Culture. One argument in the debate was that men were told that they would not be disadvantaged because they could not get pregnant and would therefore not be affected by the loss of earnings; their service would compensate for this.

JK: Nevertheless, I think it is right that there is no more conscription, because it was connected with constraints. There is still a difference whether one can chose or not.

An acquaintance once told me about his medical examination and what an interference into his physical self-determination this meant for him. Having to undress without wanting to and to have his body and mind evaluated by somebody in regard to their usability for military purposes. Right down to a look into his bumhole.

MP: I don’t harbour sympathy for the German army for it having problems to find young recruits, that would be ridiculous. But at the same time there is no tradition of a volunteer army in Germany, as is the case in the USA.

That puts into question even more the existence of the already questionable institution of the Bundeswehr in Germany, with its problematic history, it’s establishment out of the Wehrmacht and the lack of openly discussing this part of it’s history, let alone repenting and overworking its’s structures.

JK: Instead, we have the fashion army of people in camouflage on the streets. There is a lot of women’s fashion in camouflage, I find that interesting. Is this the conquest of a field from which they were excluded for a long time and where they still find it structurally more difficult to enter or at least to assert themselves? Why is camouflage so hip?

MP: I am not sure. I could imagine that it is actually a concession in the direction of objectification through the male gaze. It is perhaps too banal, but -.

JK: Why, because that’s a fetish, a woman in uniform?

MP: Exactly, because that is a fetish. What lacks the men in uniform? A pinup in uniform. But of course a pinup doesn’t wear that much.

JK: But there are camouflage bras, there are camouflage panties, besides outerwear there exists actually a lot of lingerie in this pattern.

MP: Another thing that comes to my mind at the question of women’s service at arms: in Israel there is compulsory military service for women.

JK: At least two years, which is a really long time.

MP: In Germany in the end, it was nine months, in the GDR Army it was 18 months, and in the Red Army there were a lot of women in the Second World War, famous markswomen, who were then also used by propaganda. I don’t know too much about it, but I could imagine that it also came from a communist desire for equality, equality in the sense of: everyone is male.

*Barbara Sichtermann: „Von einem Silbermesser zerteilt-“ Über die Schwierigkeiten für Frauen, Objekte zu bilden, und über die Folgen dieser Schwierigkeiten für die Liebe, aus: Weiblichkeit. Zur Politik des Privaten., Verlag Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin, 1983

**Klaus Theweleit: Männerphantasien, Bd. 1: Frauen, Fluten, Körper, Geschichte, Rowohlt, 1977

at your throat / at your feet

at your throat / at your feet  In Arms

In Arms  Business Up Front Party In The Back / Detail

Business Up Front Party In The Back / Detail  Business Up Front Party In The Back / Detail

Business Up Front Party In The Back / Detail

Business Up Front Party In The Back / Detail

Business Up Front Party In The Back / Detail  Business Up Front Party In The Back / mit Philine Kuhn

Business Up Front Party In The Back / mit Philine Kuhn  Business Up Front Party In The Back / Detail

Business Up Front Party In The Back / Detail

Yvan Eht Nioj / mit Martin Schuster

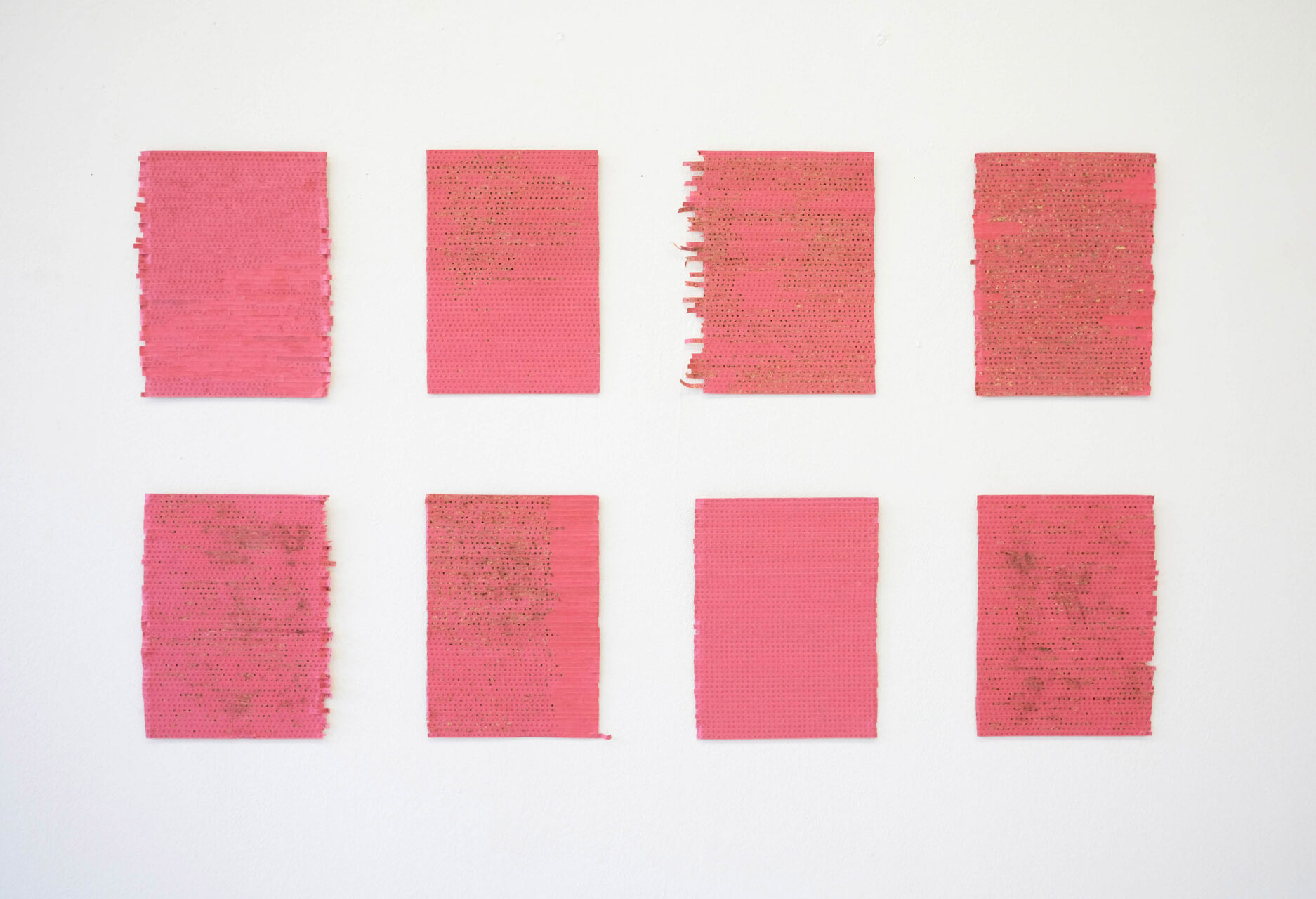

Yvan Eht Nioj / mit Martin Schuster  Loveletters

Loveletters  For men, for the body / mit Robert Müglitz

For men, for the body / mit Robert Müglitz  Wrecking Ball

Wrecking Ball  Die Gang

Die Gang

nature vs. nurture / Lady Shave

nature vs. nurture / Lady Shave  Your Perfect Partner

Your Perfect Partner